The Project

Why study Whale Sharks?

At the end of the 1980’s when the numbers of divers travelling to Galapagos began to increase dramatically I was fortunate to be one of the pioneers dive masters that dived the remote northern islands of Wolf and Darwin.

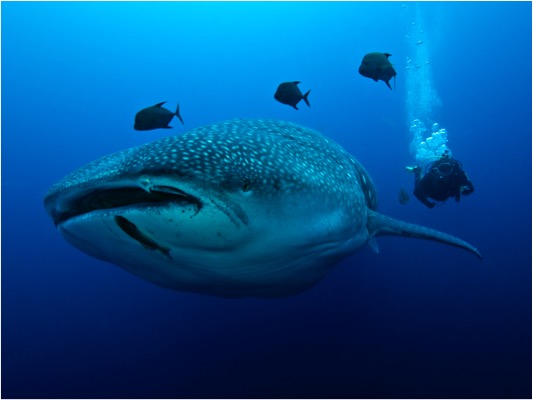

My first encounter with a whale shark shortly after was a revelation. Despite occasional sightings no one was truly aware of the numbers of whale sharks that frequented particularly Darwin Island.

I was surprised at how little was known in general about the species, not only in the Galapagos but in general worldwide. My background in the physical sciences, Geology and Physical Geography made me curious about the natural history of this ancient species, like so many marine species, more a remnant of a bygone era.

I became more aware of how whale sharks had been exploited historically and also how industrial fishing both targeted and incidental was beginning to seriously affect certain populations. With this came the realisation that without baseline data and at least a rudimentary understanding of their life cycle there is no manner in which we can create the platform, legal and physical to protect them.

The ensuing years we collected data about seasonality, frequency of sightings, sex and behaviour but with the realisation that we needed to expand our area of study and findings a different approach was needed and the Galapagos Whale Shark Project launched.

Some more details

The Galapagos Marine Reserve, which straddles the equator approximately 600 nautical miles from the coast of Ecuador, is one of the largest marine reserves in the world. Its protected waters extend 40 nautical miles from a baseline connecting the major islands covering a total area of 130,000 square kilometres of Pacific Ocean and featuring a dynamic mix of tropical and Antarctic currents and rich areas of upwelling. Consequently, the Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR), contains an extraordinary range of biological communities, featuring such diverse organisms as penguins, fur seals, tropical corals, and large schools of hammerhead sharks. The GMR has a high proportion of endemic marine species – between 10 and 30 % in most taxonomic groups – and supports the coastal wildlife of the terrestrial Galapagos National Park (GNP), including marine iguanas, sea lions, flightless cormorants, swallow-tailed gulls, lava gulls, waved albatross and three species of booby, among others. It also appears to play an important role in the migratory routes of pelagic organisms such as marine turtles, cetaceans and the world’s largest fish, the whale shark, Rhincodon typus.

The whale shark, which reaches a maximum reported length of 20 meters, was first described by a British naturalist, Stephen Smith, from a specimen from South Africa, in 1828. Since its discovery, the same species has been observed on a global scale, occurring in all tropical and warm temperate seas with the exception of the Mediterranean. Its distribution is reported to be from approximately 35–40° N to 30–35° S. The whale shark is mainly a pelagic, (open ocean), species that periodically comes close inshore for reasons as yet not fully understood, but apparently related to feeding and/or reproduction.

Listed as Endangered in the IUCN 2016 Red List, whale sharks are threatened mainly by fishing activity. Traditionally hunted for their liver oil and for waterproofing wooden boats they are now being widely sold for their characteristic white meat (referred to as “tofu shark” in Taiwan) and whole fins have been sold for as much as $15 000 each in China (CITES Prop. 12.35). Rapid reductions in numbers caught per unit effort have been seen in several areas where they have been fished including India and Taiwan, indicating that local populations are particularly susceptible to over fishing. Slow growth, late sexual maturation and potentially low reproductive rates mean that localised populations are unlikely to recover after collapse due to fishing. Nations currently involved in the exploitation of whale shark products include China, Indonesia and Taiwan with illegal catches and/or non-targeted fisheries still occurring in India, Philippines, Japan, Madagascar, Mozambique, Korea and Taiwan.

Whale sharks are capable of broad, trans-oceanic movements (timed with strong seasonal fidelity to feeding sites such as Gladden Spit in Belize, Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia and Darwin and Wolf islands in the Galapagos from mid June until late November (Green, pers. obs.) Very little is known about their biology and ecology, and their movements, particularly in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

Whale sharks feed predominantly by filter feeding on a wide variety of planktonic (microscopic) organisms but have been observed lunge feeding on nektonic (larger free swimming) prey such as schooling fishes, small crustaceans, and occasionally juvenile tuna and squid. They are generally solitary but are occasionally found in aggregations of several to over 100. e reason for this is unknown but it is assumed to be for feeding. From evidence gathered in the Galapagos during a 30-year period, strong sexual segregation would appear to occur as in many of the areas where whale sharks aggregate. At this moment in time however, Galapagos is the only population that shows such a predominant (over 99%), female inclination.

Whale sharks are ovoviviparous with eggs hatching within the female’s uteri and the female giving birth to live young. A 9m female was caught in Taiwan with 300 young suggesting that the whale shark is the most prolific of elasmobranches.

Sparse information exists on reproductive and pupping grounds, in addition to our lack of information on migratory routes and home range sizes.

Objectives of the project

The overall objectives of this study are:

- At a local level, understand the importance of the Galapagos Marine Reserve to whale sharks.

- At a regional level, increase our knowledge of whale shark migratory patterns and reproductive behaviour.

- Raise global awareness of whale sharks as charismatic ambassadors for sharks and marine conservation.

- Ascertain the feasibility of creating protected areas both on a regional and global level.

- Document the natural history using underwater video, diving and eventually by submersible.

In order to achieve these objectives, we aim to:

- Build the local capacity in the study of whale sharks, through the use of acoustic and satellite technology and collaborative analysis of results.

- Characterise the population abundance and structure of whale sharks visiting the GMR using photo / video identification.

- Assess the seasonality of whale shark occurrence within the GMR with relation to environmental triggers such as changes in major currents.

- Determine the migratory movements taken by whale sharks in the Eastern Tropical Marine Corridor region by use of MiniPAT, SPOT and SPLASH

- Determine occurrence of aggregations and reproductive behaviour within and outside the GMR.

- Raise local awareness of the importance of the GMR for migrating pelagic species using whale sharks as an example, with emphasis on schools.

- Raise global awareness of the importance of the oceans, as a finite resource and the basis for a healthy planet, that are being plundered and polluted.

You would like to READ MORE about the project?

Go BACK to